Southern Ocean Time Series: Caring for your sediment trap

9 April 2025

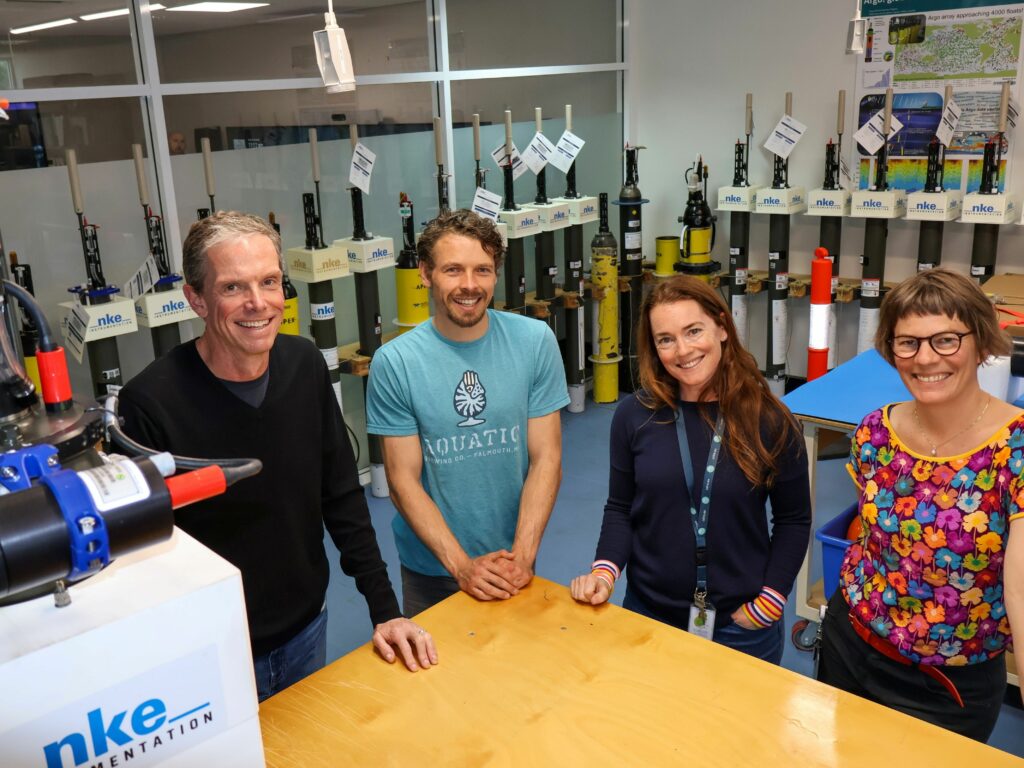

Every year, members of the IMOS Southern Ocean Time Series (SOTS) team travel on the CSIRO research vessel (RV) Investigator to recover the deep-sea moorings that are the principal part of the facility, and deploy instruments to collect observations for the upcoming year. The SOTS observatory is one of the few comprehensive Southern Ocean sites globally for measuring continuous ocean and atmosphere data.

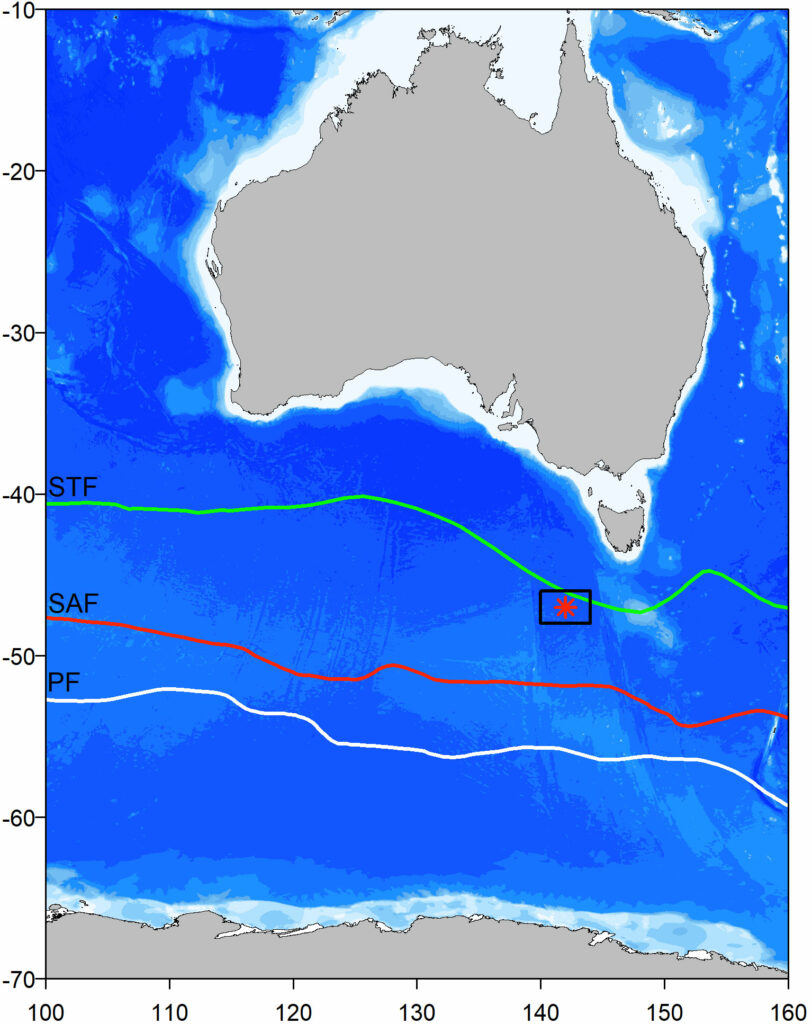

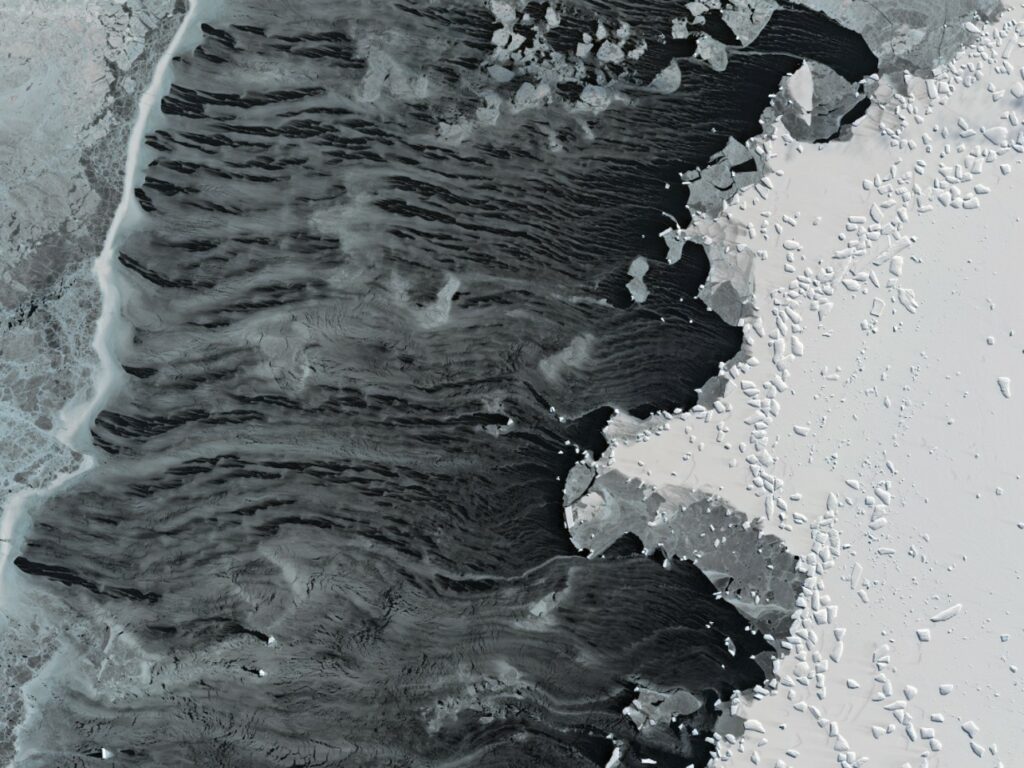

Located about 500km south-west of Hobart, the SOTS observatory is in the sub-Antarctic zone, a region of the Southern Ocean known for extreme weather conditions including large waves, strong currents, and severe storms. Here processes controlling the air-sea exchange of heat, moisture, and carbon dioxide are both intense and relatively poorly understood.

A lot of hard work goes on during the voyage to make sure everything goes off without a hitch, but before the voyage there are months of work that goes into preparing the equipment to spend 12 months thousands of metres below the ocean surface.

Three deep-sea sediment traps are a main aspect of the SOTS program and the longest running component, having first been deployed in 1997. They are stationed at 1000m, 2000m, 3800m below the ocean’s surface at the SOTS site (nominal location of 47oS, 142oE).

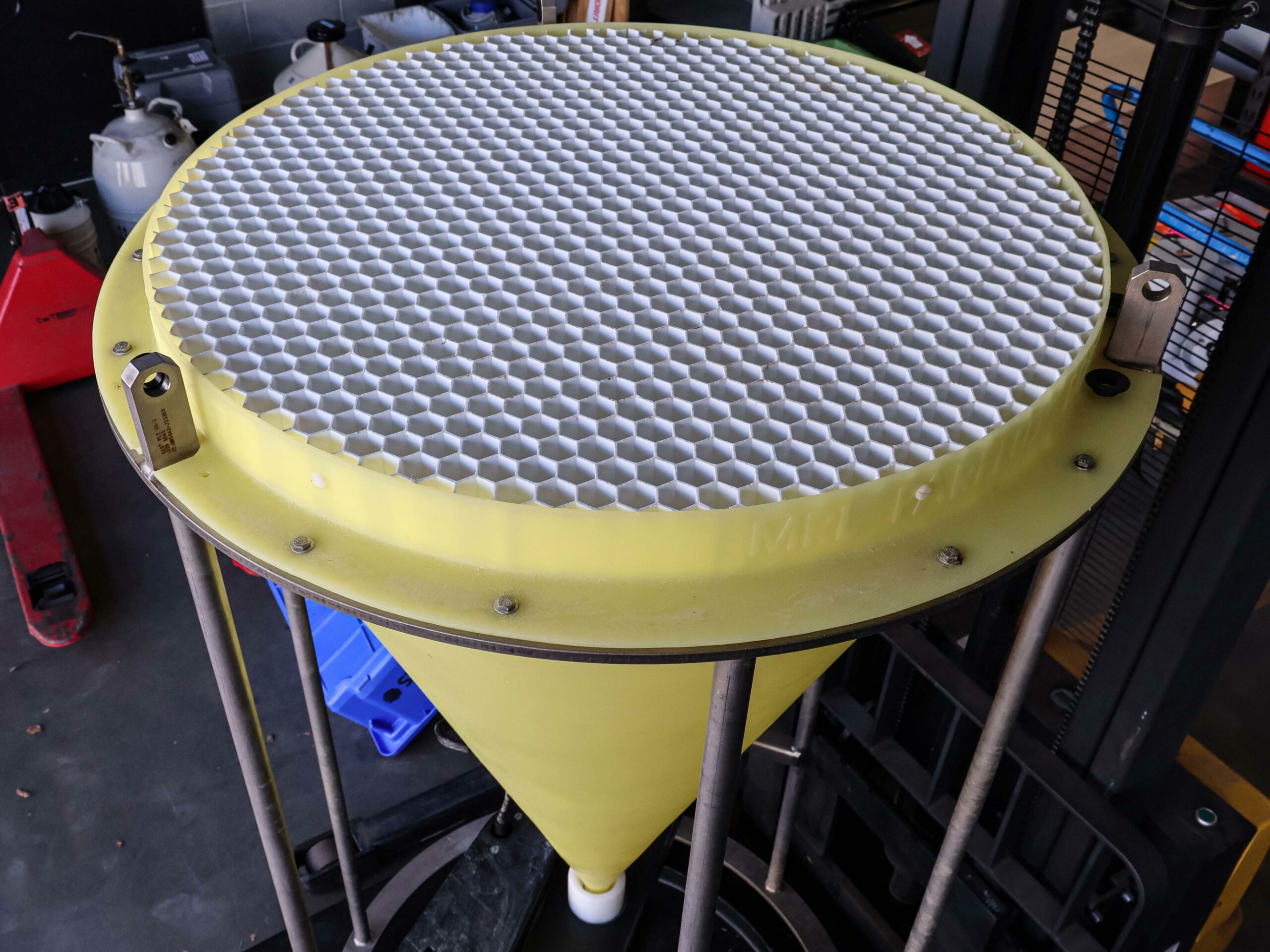

The traps are large funnels designed to collect sediment sinking from the ocean surface to the deep ocean, with a rotating carousel that allows the collection of multiple samples. This enables study of the transfer of carbon and nutrients to the ocean interior via sinking particles, also known as the biological carbon pump. Researchers are also interested in the ‘transfer efficiency’, which is the fraction of organic matter that remains after being consumed as it travels between the surface layers and depth.

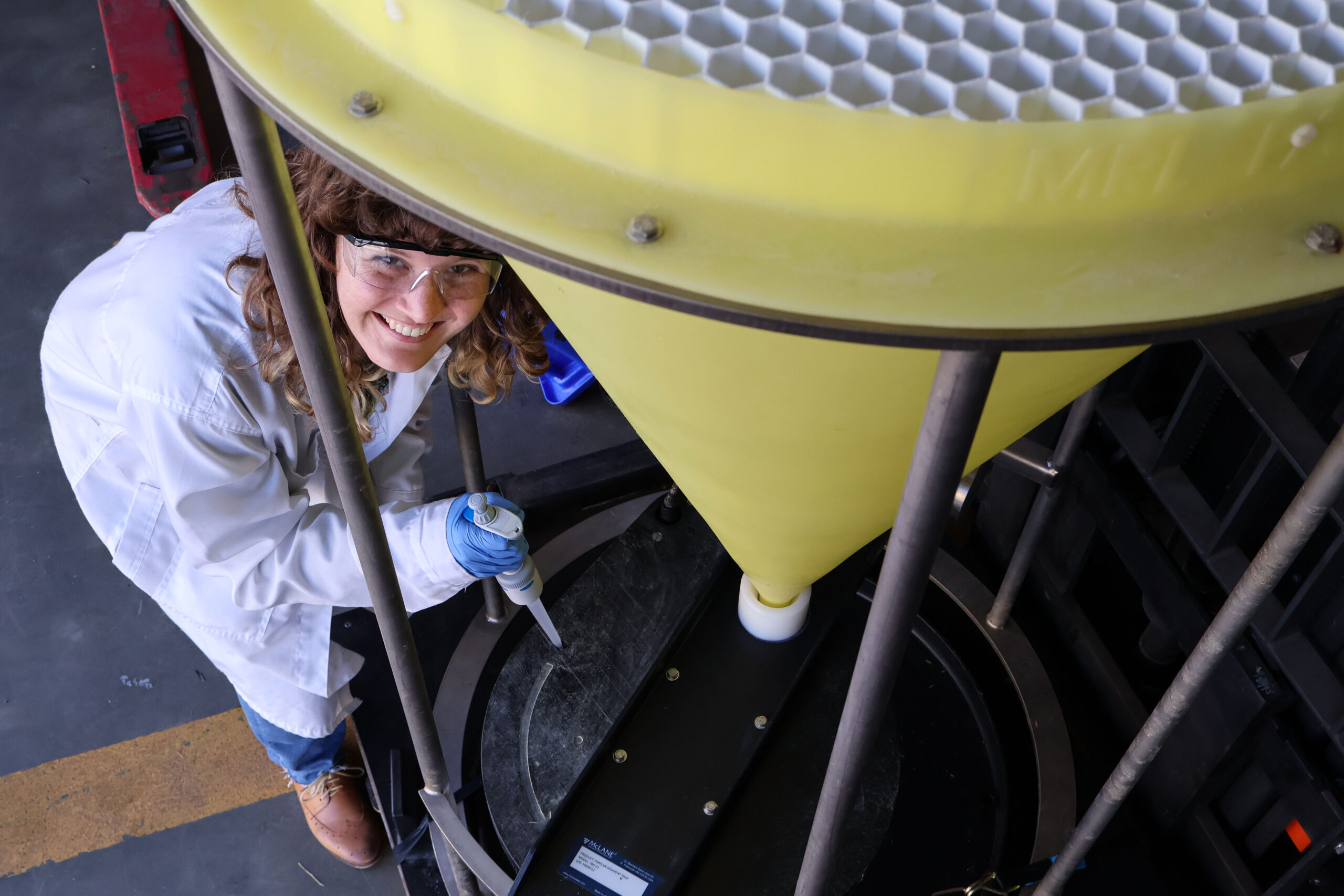

To keep the sediment traps working for another 25 years, they go through various preparation and maintenance steps before being deployed into the deep ocean. That’s the job of Gemma Woodward, AAPP’s Marine Carbon Analytical Chemist:

“The first task is to clean the gear plates of the carousel. These are cleaned upon recovery before they go into storage for 9 months but are given another clean to make sure no ocean debris remains. The gear plates are taken apart and all the constituent parts are cleaned – including ball bearings and bottle seals – before being carefully put back together.

“A performance test is then carried out on the seals. These are placed into their dedicated slots around each bottle hole and the bottle holes are filled with water. After an hour, the water levels are checked to see whether the seals have allowed water to leak. This is to check for fast leaks so that during deployment no solution spills onto the deck and becomes a danger to the crew.

“Once the gear plates have been reattached to the sediment trap frame, the sample bottles are screwed into the gear plates and filled with water. Another leak test is carried out, this time the entire sediment trap is turned on its head to see whether the bottles leak. The sediment traps are left overnight to check for slower leaks between the bottles and the gear plates.

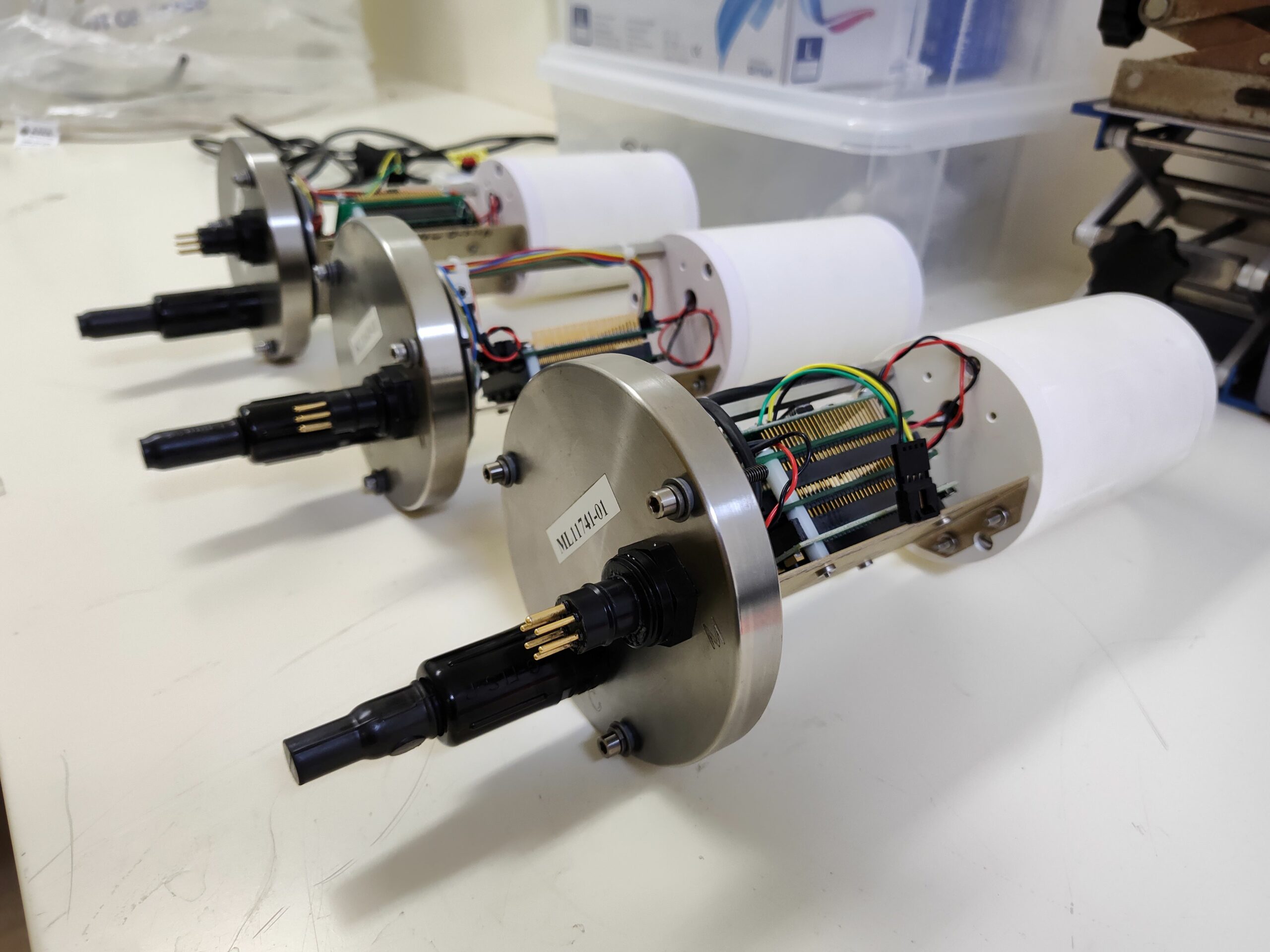

“When the sediment traps have been declared leak free, attention shifts to the electronic part of the sediment trap. Each sediment trap has a controller and a motor; the controller acts as the brain telling the motor when to rotate the gear plates so a new sample can be started. Because the sediment traps are moored in the deep ocean the controller casing has to be watertight so it contains several o-rings and these are checked for wear and tear before being greased to ensure they create a seal.

“The batteries in the controller are replaced, and because the controllers contain compasses the batteries need to be degaussed before installing them. This involves circling each battery with a degaussing wand to remove the magnetic field sometimes found in batteries. If the batteries were not degaussed then the 14 batteries could create a large enough magnetic field to disrupt the compass.

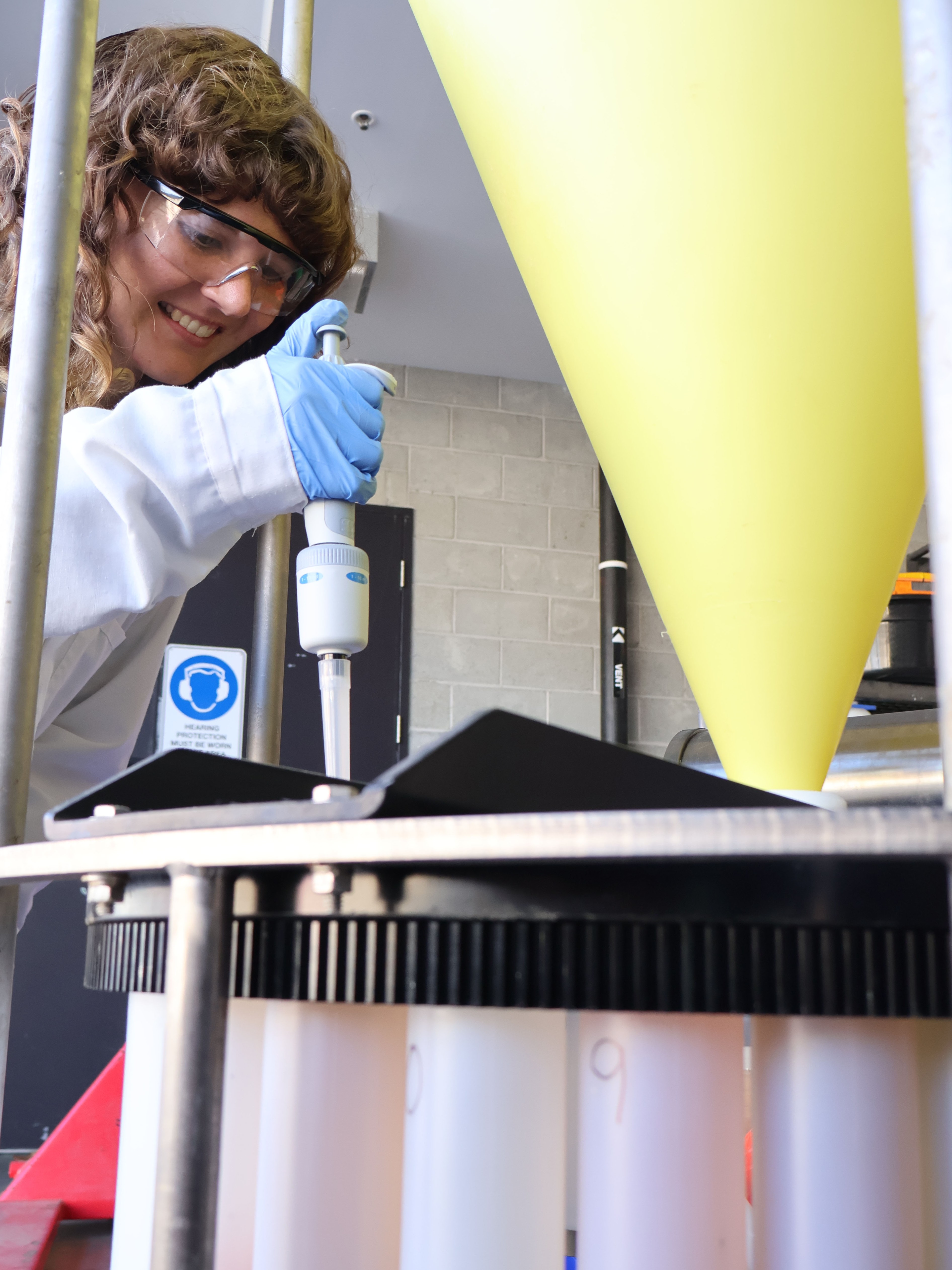

“Finally, the bottles are filled with artificial brine and a preservative. The brine consists of seawater and added salts to increase the density and ensure there is no mixing between the liquid in the sample bottles and the surrounding seawater once the sediment traps have been deployed. The preservative ensures nothing decays while the sediment traps are at sea and any organisms that fall in remain in a good condition.”

With the traps now ready for deployment, they are safely transported to the shipping container and lifted onto the ship. They were expertly deployed by the CSIRO moorings team and crew on RV Investigator and will hopefully return full of samples on next year’s voyage.

The Integrated Marine Observing System (IMOS) SOTS site is operated through a partnership between IMOS, CSIRO, Bureau of Meteorology, and the Australian Antarctic Program Partnership (AAPP). IMOS and the CSIRO Marine National Facility are national research infrastructure supported by the Australian Government’s National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy (NCRIS).

This research was supported by a grant of sea time on RV Investigator from the CSIRO Marine National Facility.