Meet the Predator Observers

After 14 days transiting from Hobart to the south-west corner of the survey area and 10 days running transects north-west of Mawson Station, the Predator Observer team has recorded 445 sightings of marine mammals. The sightings have included Antarctic blue, fin, sei, sperm, humpback, Antarctic minke, killer, and pilot whales, as well as crabeater and fur seals. So far, humpback whales have been the species most often sighted, accounting for almost 50% of our current numbers.

The other research teams on RV Investigator are working to estimate and understand the krill population off Mawson, so that CCAMLR can set precautionary catch limits for the potential krill fishery. However, as many Antarctic predators rely on krill as their primary food source, the Predator Observer team is working to determine the size and species composition of the predator population in the area, to ensure that any catch limits explicitly account for their needs. There are four observers recording marine mammals, Kym Reeve (Team Leader), Josh Smith, Maria Isabel Garcia-Rojas and Angus Henderson; while Jeremy Bird records sea bird observations. The marine mammal team conducts 12 hours of observations during daylight (weather permitting) while the ship is underway, and rotates through different positions every 40 minutes. During each rotation, two observers search for marine mammals in our custom-designed observer boxes placed outside on Deck 5 of the ship, while the third team member sits inside in the warmth of the ship’s Bridge logging sightings. The observers alternate between scanning the water using their naked eye and using a pair of hand-held binoculars. When an animal is sighted, usually by seeing the blow first, we use radios to communicate the necessary information to our data logger in the Bridge. When it’s busy, each observer will be tracking multiple sightings at a time, while still looking for new sightings. During these times our data logger not only records the sightings, but also helps us keep track of the different sightings and prompts us for missing information.

The survey transects run perpendicular to the continent, so we move north away from the ice edge every several days. We all look forward to returning to the southern parts of the transects where we are more likely to observe wildlife including seals, penguins, killer and minke whales. This is also the area where we can admire the numerous large icebergs, surrounded by their broken bergy bits, and new forming sea-ice known as pancakes. Sea-ice is a key habitat that supports the Antarctic food web. As it freezes, sea-ice brings nutrients to the surface where light enables plankton to bloom, and it also provides shelter and food for zooplankton. The algae that grow inside and under the ice flows provides food to juvenile krill before they grow strong enough to feed throughout the water column. It is therefore not surprising that we have also sighted Antarctic blue, humpback and sei whales along the sea-ice edge where there is likely more krill for these beautiful giants to forage on, and gain as much weight as possible before the summer bloom dissipates.

Each day is very different and it keeps us on our toes. Rare calm days when the sea is flat and the sun is shining provide amazing conditions for sighting marine mammals. More commonly, however, conditions are overcast and windy. At times dense fog patches and snow storms limit visibility to under 1000m around the ship, and high seas with waves greater than 6 metres and winds above 30 knots prevent us from conducting visual observations. Sightings have been patchy, ranging from days where the ocean is quiet and no animals are insight, to periods when the ship sails through high productivity ‘hot spots’ and observers are bombarded with numerous whale sightings. Last week on the 23rd of February, for example, we recorded 102 sightings which included over 186 animals. During the day, we encountered very high densities of whales recording up to 45 animals along a 10 nautical mile segment of the transect, which is equivalent to detecting an animal every two minutes!

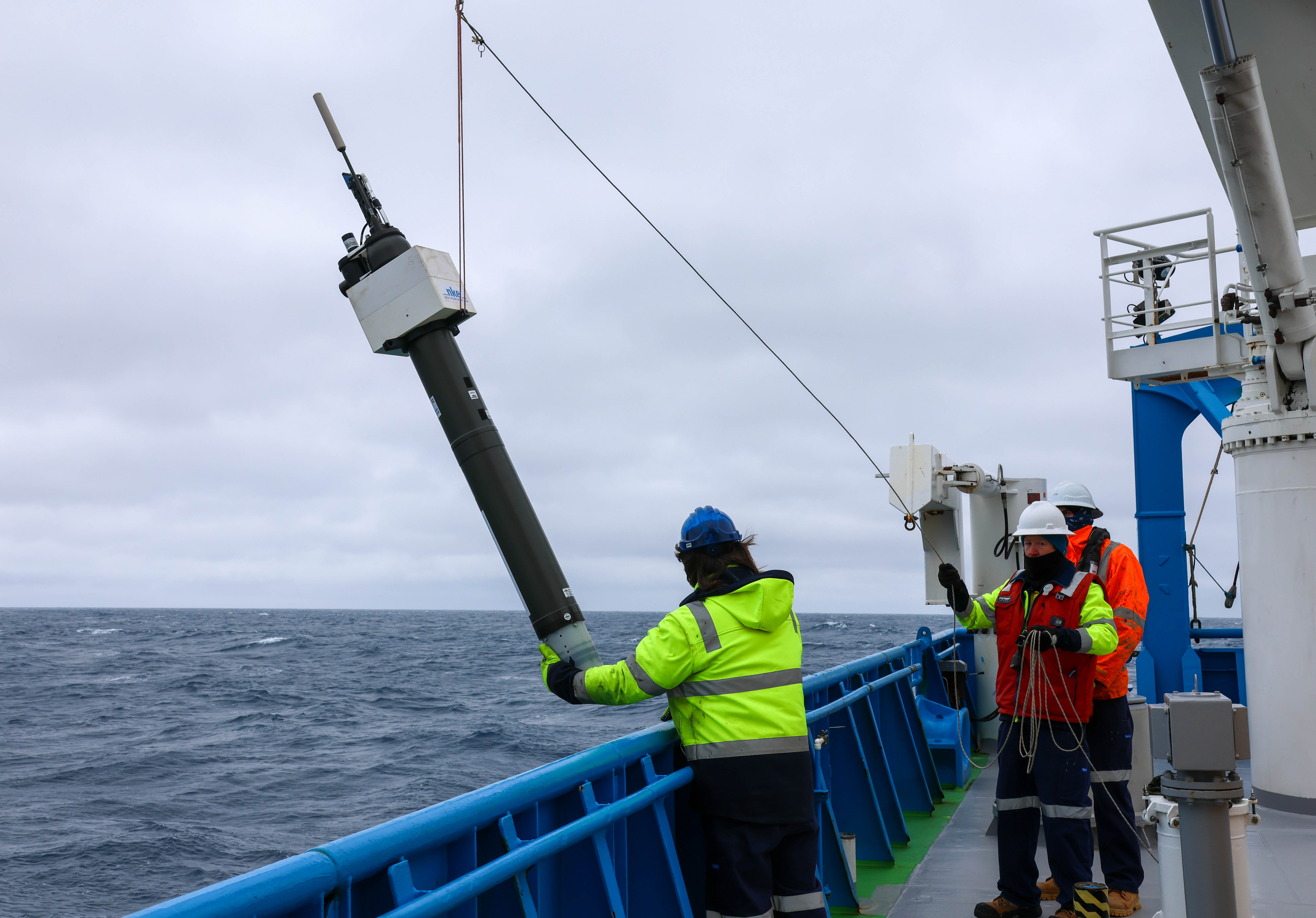

However, as most marine mammals spend a large part of their lives underwater, they can be easily missed by visual observers as they pass by on a moving vessel. We are therefore also deploying sonobuoys which detect underwater sounds, recorded back on the ship, that will be analysed once we return to Hobart. The sonobuoys can detect distinctive sounds from at least 13 different marine mammal species. And for some species, we can detect calls from much further away than they can be visually sighted by observers. For example, the calls of Antarctic blue whales are so low frequency (humans can’t even hear them) that they can be detected from over 850km away! Once analysed, these recordings will give us a clearer picture of the species present in the survey area. They will as help to fill in some data gaps, as sonobuoys can record sounds at night and in poor weather such as high seas, fog and snow storms, all conditions that limit visual observations.

The TEMPO voyage is conducting critical research, and we all feel privileged to be part of this scientific expedition. We also can’t wait to see what else Antarctica has in store for us for the remainder of our time at sea.