Securing Antarctic research: the ’roundabouts’ of science funding

by Prof Nathan Bindoff, June 2025

Much has changed over the last three decades in my line of work as a physical oceanographer and climate scientist.

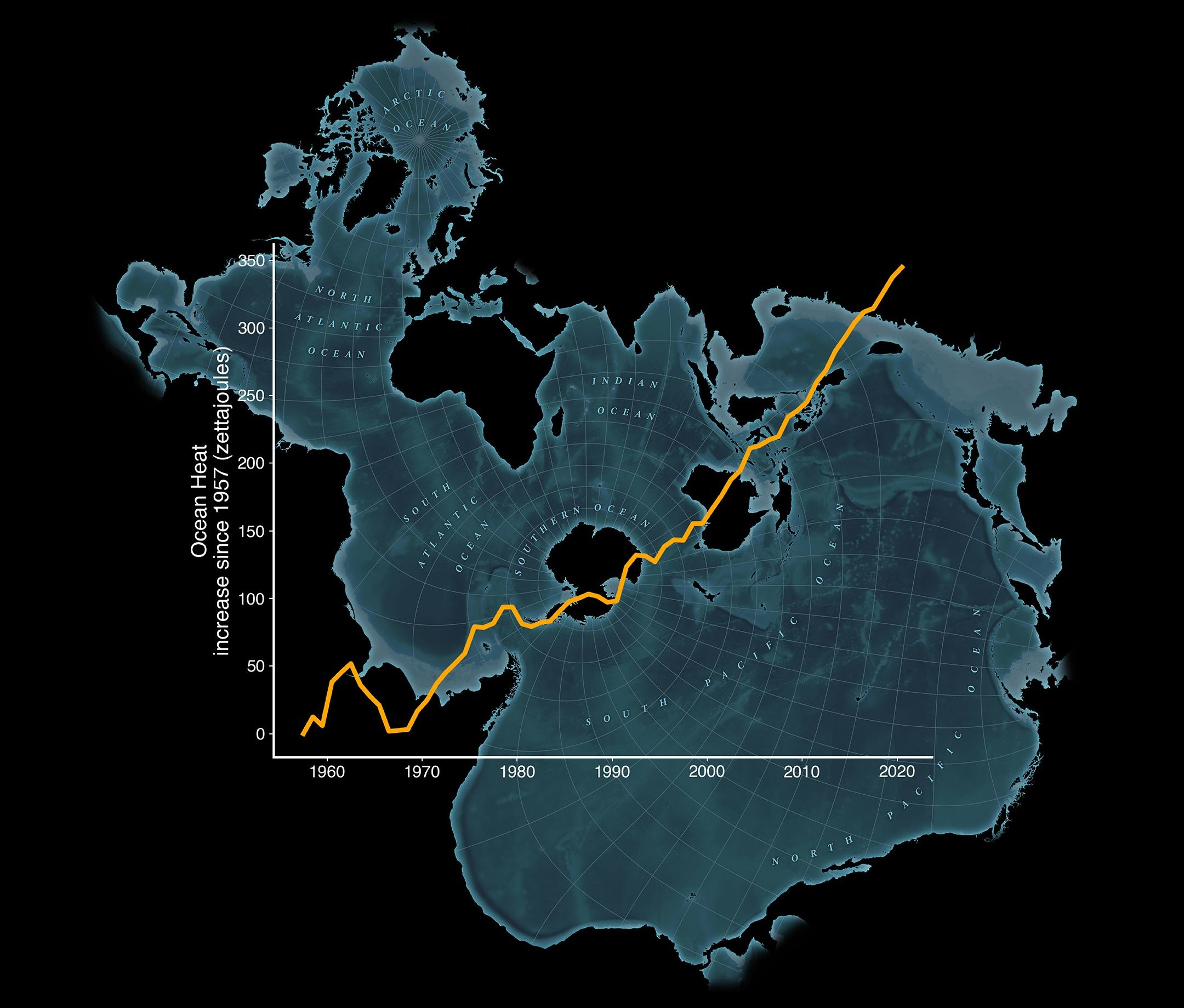

My research aims to detect and understand the signals of change in the oceans – like oxygen levels, temperature and salinity – and what causes them.

Back in the eighties, the question of whether the state of the oceans had changed was completely open and not attributed to human influence.

Since then, there has been a seismic shift in science towards a much deeper recognition of the oceans’ role as a key driver in the global climate system and the impacts of our emissions.

Twenty years ago, there was another turning point when the scientific community realised that Antarctica was not the ‘sleeping giant’ we’d assumed, and that ice sheet loss is an increasing contributor to sea level rise.

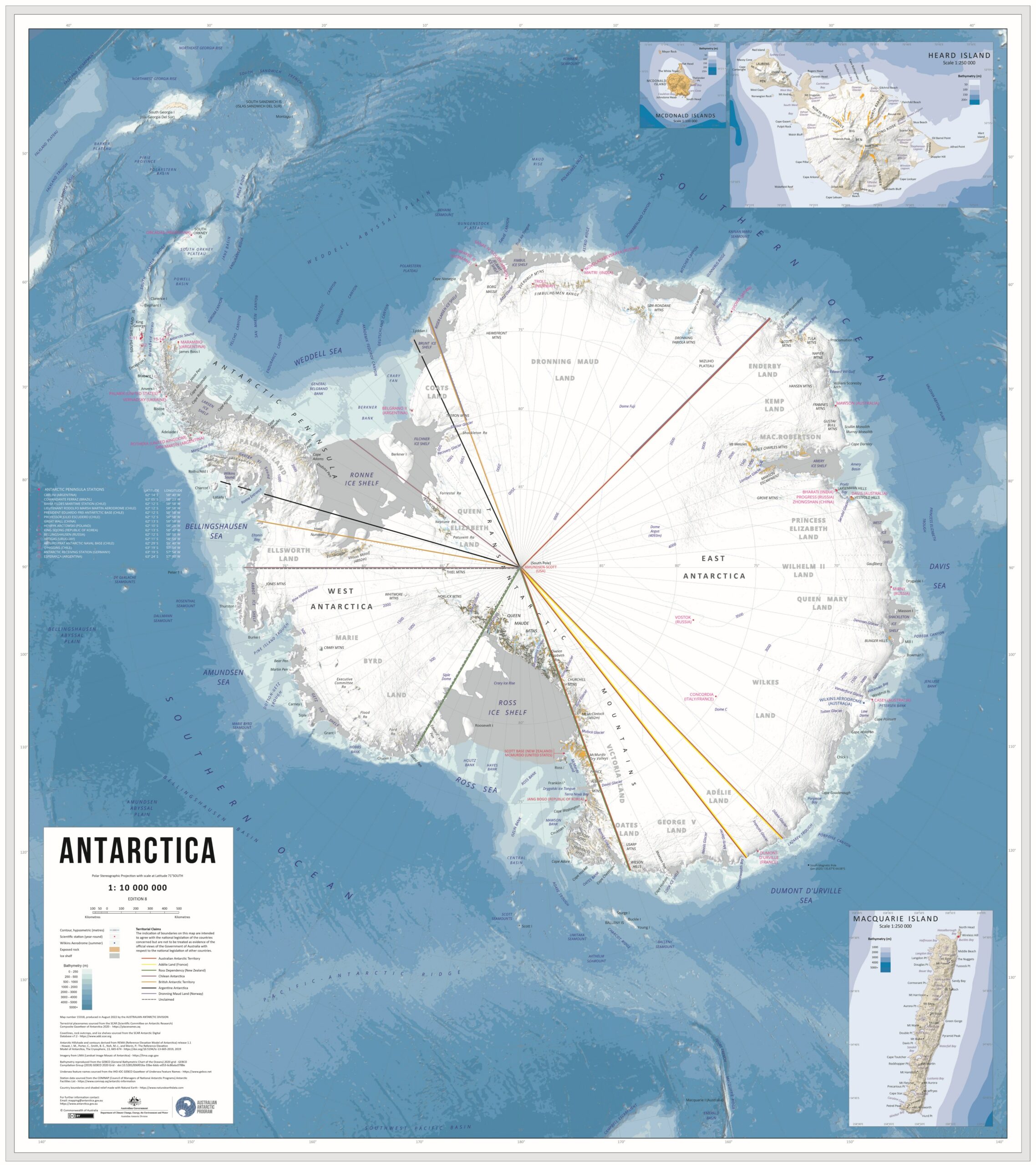

However, what hasn’t changed over that time is that Australia still lacks a sustainable system to provide long-term funding certainty for Antarctic and Southern Ocean research, especially in the 42% of the entire continent we regard as Australian Antarctic Territory.

The total annual budget for Australian Antarctic science is currently around $39.5 million. While that may sound like a lot, considering the scale and urgency of the task, it’s not. That’s about the cost of upgrading one traffic roundabout or building a new recreation park.

This funding is spread across five different streams and doesn’t include logistical costs like shipping or research contributions from the university sector (which accounts for 75% of Australia’s Antarctic research effort) and Commonwealth science agencies like the Australian Antarctic Division, CSIRO, Geoscience Australia and the Bureau of Meteorology.

Three of those five streams are university-based and due to end soon. Without intervention by the Australian Government, one will terminate within a year, and the other two within the next four years.

It would make sense to merge the three funding streams together under one contract, while expanding the overall budget and making it ongoing – as has been recommended by various Parliamentary inquiries.

On top of that, funding to do Antarctic research is not necessarily connected to how you’re going to get there to do it – gaining logistical support under the Australian Antarctic Program falls under a separate process.

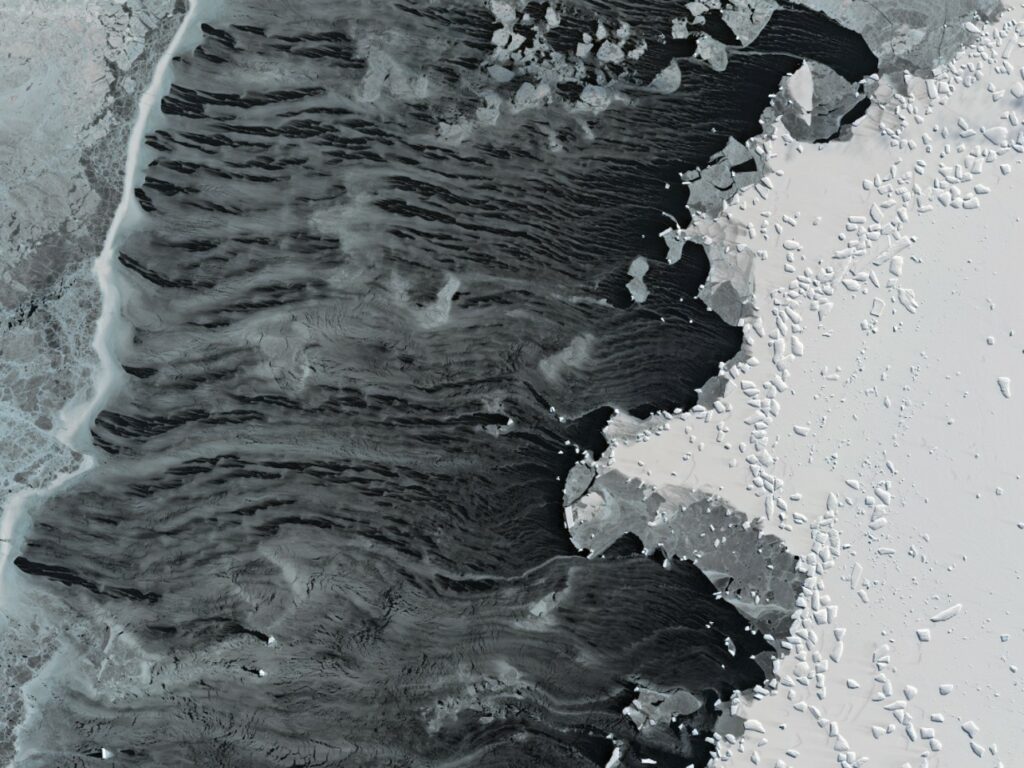

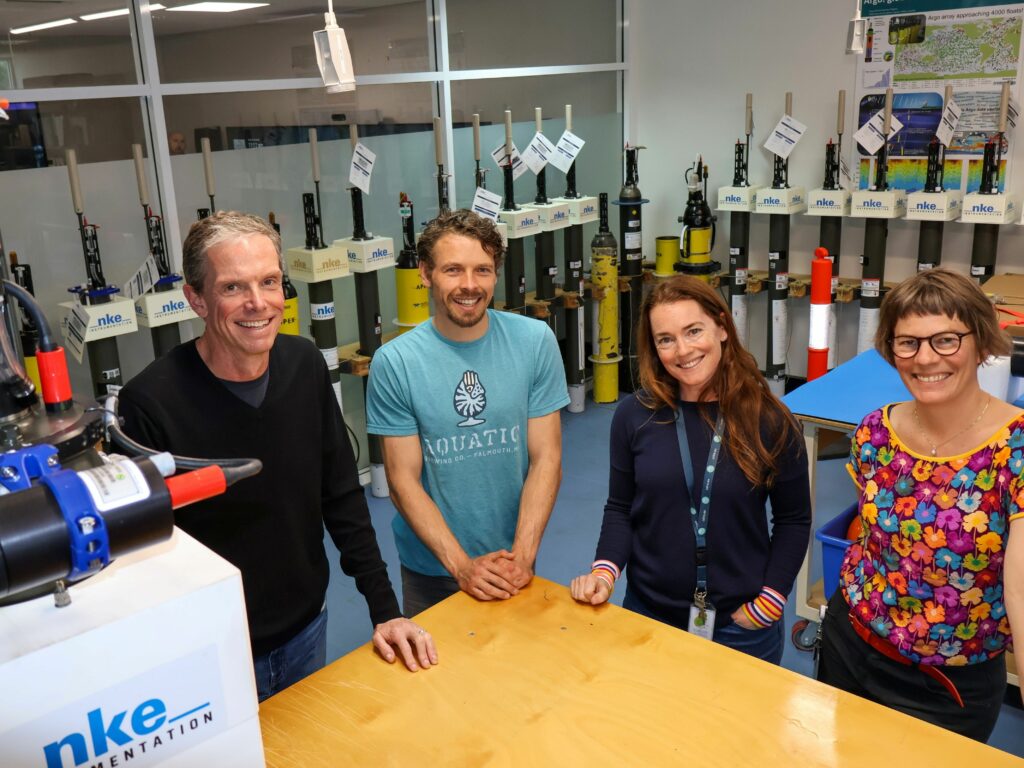

In early May, sixty scientists returned to Hobart from a two-month voyage investigating the Denman Glacier in East Antarctica, its vulnerability to the warming ocean and its likelihood of making a larger and faster contribution to sea level rise within the next few decades.

As the first dedicated science voyage for Australia’s new icebreaker RSV Nuyina, this was a highly collaborative and successful science mission between four leading research organisations that’s been years in the making.

It was also the first substantive marine science voyage by the Australian Antarctic Program since 2017, which means eight years have elapsed during a period of dramatic change in Antarctica, especially in sea ice.

There is a growing disconnect between the urgency of our research in Antarctica and Australia’s ability to deliver science for the national and international interest – especially as the capability and commitment of other nations, like the US, may be starting to falter.

It’s not because we don’t have the tools and infrastructure. We do. In the recent voyage, RSV Nuyina proved to be a research vessel of world-class scientific capability.

It’s more about how we choose to use our single Antarctic vessel and its crew to meet the competing priorities of multidisciplinary science on the one hand, and supporting Australia’s research stations with cargo, fuel and personnel transport on the other.

The difficulty is that a single ship is not able to do both adequately. Understandably, Antarctic logistics to support lives and safety will always trump science. A second ship for doing resupplies would free up RSV Nuyina for more science days at sea and build resilience in the Australian Antarctic Program.

After five years leading the Australian Antarctic Program Partnership – a consortium of Australia’s government research agencies led by the University of Tasmania (UTAS) – I’m standing back to pursue a new climate project to develop near real-time indicators of the oceans’ response to reducing emissions.

Having just stepped off the icebreaker, my colleague and sea-ice expert Professor Delphine Lannuzel is taking the reins as program leader. The next generation of science leaders will reshape Australia’s research efforts at this critical time for Antarctica’s future.

I’m thrilled to see our scientists back on shore – many of them early-career researchers on their first voyage, most from UTAS – their faces shining with wonderment and enthusiasm. But I do wonder if funding for future voyages will be up to the task.

Now more than ever, we need the power of partnerships to accelerate our research in Antarctica and the Southern Ocean and keep pace with the rapid changes happening there – as if all our lives depended on it.

- Prof Nathan Bindoff led the Australian Antarctic Program Partnership from 2020 to 2025, based in the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies at the University of Tasmania in Hobart