Seeding clouds: the power of partnerships in Antarctic research

12 April 2023

An international cohort of scientists is calling for more research collaboration between different countries and disciplines to properly understand how clouds are influenced by tiny life forms in the Southern Ocean around Antarctica.

A commentary entitled ‘Untangling the influence of Antarctic and Southern Ocean life on clouds’ by 30 authors from 11 countries was published in Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene recently.

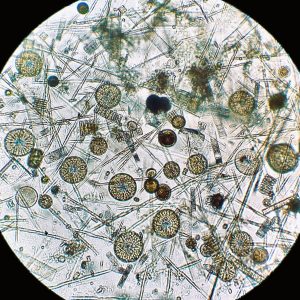

“The idea that tiny marine life forms like plankton can have a big impact on clouds is incredibly fascinating, but it’s also a crucial process in the climate system,” said lead author Dr Marc Mallet of the Australian Antarctic Program Partnership.

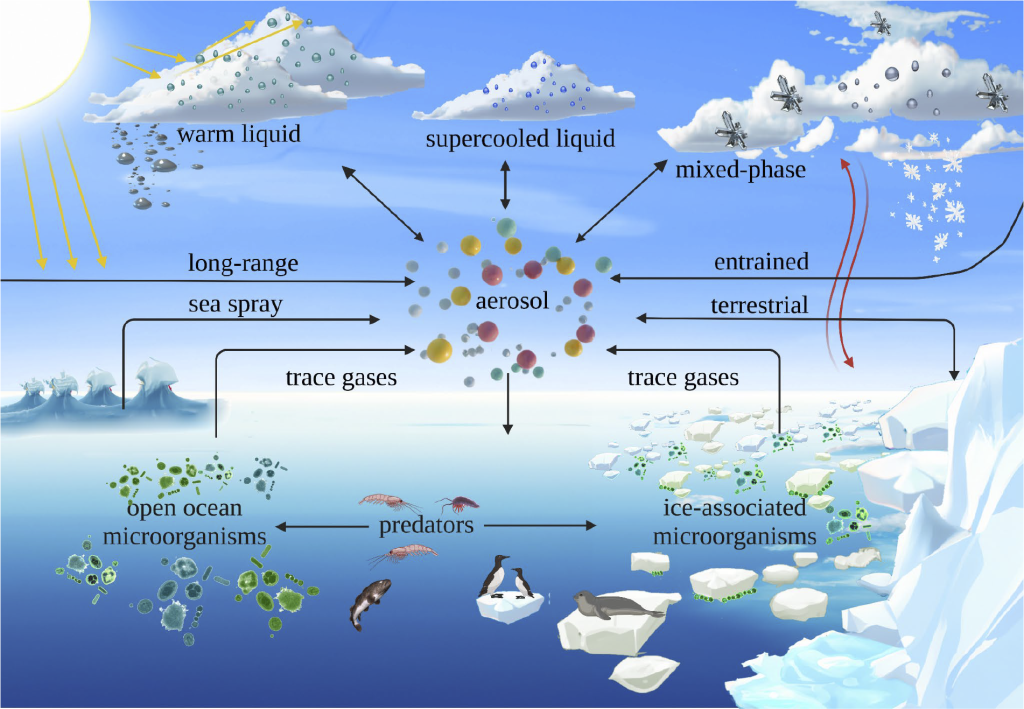

“Unlike dusty and polluted regions elsewhere in the world, the clouds of the relatively pristine Antarctic and Southern Ocean region are seeded by aerosols, tiny airborne particles, that come from the ocean itself.”

“Some of these are emitted by sea spray from breaking waves, but tiny microorganisms also emit sulfuric gases into the air that form these cloud-seeding aerosols,” he said.

“Without aerosols, clouds can’t form at all in our atmosphere. They regulate rain and snowfall, as well as how much energy is reflecting back into space from the sun or is trapped in the lower atmosphere.”

Clouded models

The commentary notes the latest generation of climate models, prepared for the recent Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC AR6), still show significant biases in the amount of sunlight reaching the surface of the Southern Ocean compared to satellite observations.

“This is a clear indication we still have a long way to go in understanding how clouds form and evolve in this region,” the authors warn.

“While meteorological processes play an important role in the energy balance of Earth’s surface, we also need to describe and quantify how biology influences the chemistry and physics of the atmosphere.”

By highlighting lessons learned from a handful of recent field campaigns, the authors also propose a number of research priorities, ranging from better understanding how marine microbes like bacteria, phytoplankton, and ice algae emit various gases into the atmosphere; to how these gases form aerosol particles; and how these aerosol particles influence cloud properties.

But the sheer size of the Antarctic and Southern Ocean region, and the complexity of the system, means that no one country or institution can fill all the knowledge gaps alone.

Power of partnerships

The authors note at least 22 fully-funded or proposed research campaigns from various nations over the next four years will explore the links between marine and terrestrial biogeochemistry and the atmosphere.

“The next few years will be huge. There are very few long-term measurements in the Southern Ocean compared to other parts of the world. We have to make sure we get the most value out of our shorter but more intensive measurement campaigns,” Dr Mallet said.

“We’ve recently launched an initiative called PICCAASO, standing for Partnerships for Investigations of Clouds and the biogeoChemistry of the Atmosphere in Antarctica and the Southern Ocean.”

“The idea is to encourage and improve global coordination and collaboration of research campaigns on Antarctic stations, in the air and at sea by sharing resources, ideas, and data,” he said.

“By unifying our efforts, we aim to provide the most comprehensive understanding of how Antarctic life influences the global climate, as quickly as possible.”

Clouds of the Antarctic and Southern Ocean region are seeded by aerosols that come from the ocean itself – sea spray from breaking waves, and sulfuric gases emitted by phytoplankton.

The Australian Antarctic Program Partnership is led by the University of Tasmania, with partner agencies CSIRO, Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies, Bureau of Meteorology, Australian Antarctic Division, Geoscience Australia, Integrated Marine Observing System, and the Tasmanian Government.