“We are addressing a critical challenge”: the future of marine ecosystem modelling

23 July 2025 — republished from Australian Centre for Excellence in Antarctic Science (ACEAS)

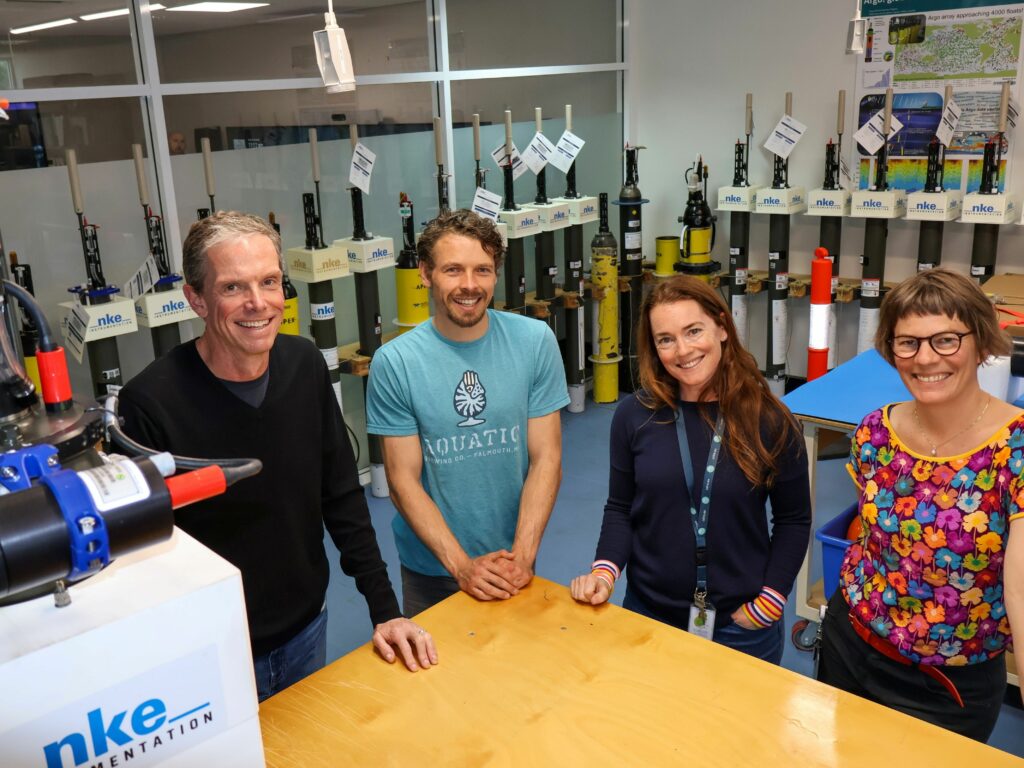

Marine ecosystem researchers from around the world have gathered in Hobart to discuss the big challenges facing those tracking and projecting how our oceans respond to climate change.

‘Advancing Regional Marine Ecosystem Modelling: from Southern Ocean to Global Perspectives: A FishMIP Regional Modelling Workshop’ was hosted by FishMIP at the University of Tasmania and supported by the Australian Centre for Excellence in Antarctic Science (ACEAS) and the Australian Antarctic Program Partnership (AAPP).

Dozens of marine ecosystem specialists from almost every continent attended in person or online, including from South Africa, Spain, New Zealand, Canada, the USA, Europe and China.

“We are addressing a critical challenge: we need to provide meaningful scientific advice to policymakers and other stakeholders about how marine ecosystems will respond to climate change, but developing these complex models traditionally takes years,” said co-organiser, Dr Kieran Murphy (IMAS/UTAS).

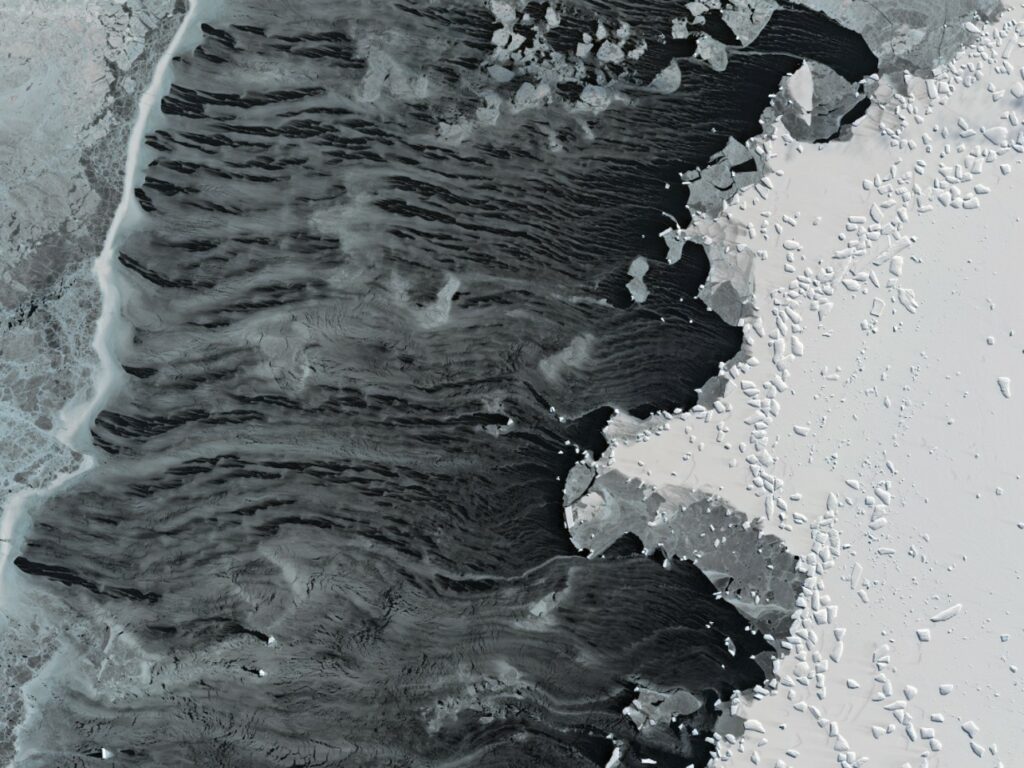

“In particular, the Southern Ocean is changing rapidly, and we simply can’t afford to spend five years developing a model when the ecosystem might have fundamentally shifted by then.”

FishMIP (led by Professor Julia Blanchard – IMAS/UTAS) is a network of more than 100 marine ecosystem modellers and researchers and seeks to answer critical questions about the future of our marine ecosystems in a changing climate.

How the models work

The computer models themselves are painstakingly built and fine-tuned by researchers using vast datasets, to create an accurate representation of real-world ocean systems and capture the impact of climate change over time – past, present and future.

The model results are constantly compared, contrasted and developed, helping to answer questions about marine biodiversity, marine ecosystem functioning, fish and fisheries and seafood supply.

For example, said Dr Murphy, they might use 50 years of historical data to evaluate the “model skill” and then project into the future.

He said while upcoming decades are the focus for short to medium-term management decisions or research questions, longer-term projections are also assessed.

“We input everything from satellite data showing sea surface temperatures to ship-based measurements of krill abundance,” said Dr Murphy.

“The outputs give us projections of how krill, fish and whale populations, as well as entire food webs might look under different climate scenarios.”

“Policymakers can then use these outputs to make informed decisions about fishing quotas or conservation priorities.”

So, what were some of the highlights of the workshop?

Workshop highlights

- An intensive focus on AI tools to develop regional models, led by Dr Scott Spillias (CSIRO). Workshop participants agreed AI had enormous potential for accelerating model development, to better provide advice to authorities responding to rapid environmental change. “We could be on the cusp of developing models and producing impactful outputs in months rather than years,” Dr Murphy said.

- Strengthening partnerships with groups like SCARFISH and the Ross Sea MPA Research Coordination Network, paving the way for maximising research impact and avoiding duplication of efforts within the Southern Ocean research community.

- Broadening the scope of models to consider including lower trophic-level, or base of the food web components and biogeochemical elements. Professor Phillip Boyd (UTAS) presented new research on the emerging field of Ocean CDR – Carbon Dioxide Removal – and its implications on marine ecosystems.

Powered by collaboration

A focus on regional perspectives, including the Southern Ocean Marine Ecosystem Model Ensemble (SOMEME) (Kieran Murphy), and priorities for modelling from a CCAMLR perspective (Andrew Constable – CSIRO/UTAS), were also highlighted. The alignment of efforts in Southern Ocean modelling was a major theme.

Dr Murphy said the sheer size of the Southern Ocean and difficulty getting there, made collaboration all the more important.

While Australia has a greater focus on East Antarctica, New Zealand is focused on the Ross Sea and the British Antarctic Survey is best placed to access information on West Antarctica.

“Having everyone together was incredibly valuable because we’re all working together on similar challenges but often in isolation,” said Dr Murphy.

“When you get marine ecosystem modellers in the same room, the conversations that happen over coffee breaks and dinner often lead to the biggest breakthroughs.”

Dr Murphy said combining efforts would lead to greater understanding of broader scale dynamics and better keep pace with environmental change.

“The ocean doesn’t respect national boundaries… we need to pool our expertise and avoid duplication if we’re going to provide the rapid, high-confidence scientific advice that policymakers need.”

“What policymakers need to understand is: the risk of inaction is enormous. We’re already seeing mass mortality events in emperor penguins and shifts in the base of the food web. We need precautionary management approaches that can adapt quickly as our understanding improves.”

Find out more about the Fisheries and Marine Ecosystem Model Intercomparison Project (FishMIP) here.