Triaxus in tow

Maya Jakes

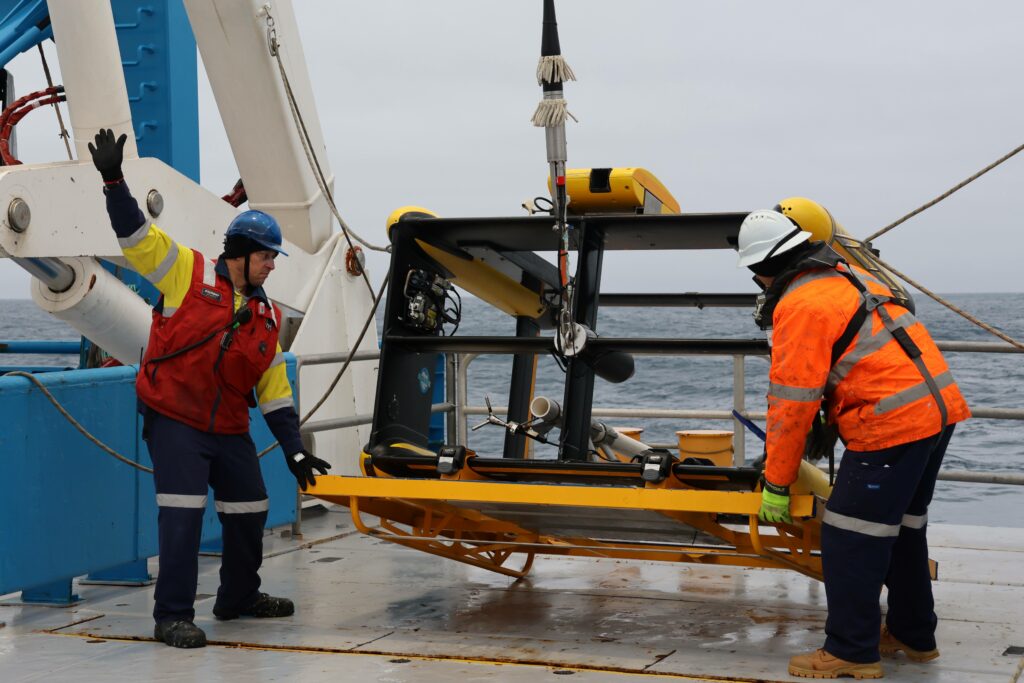

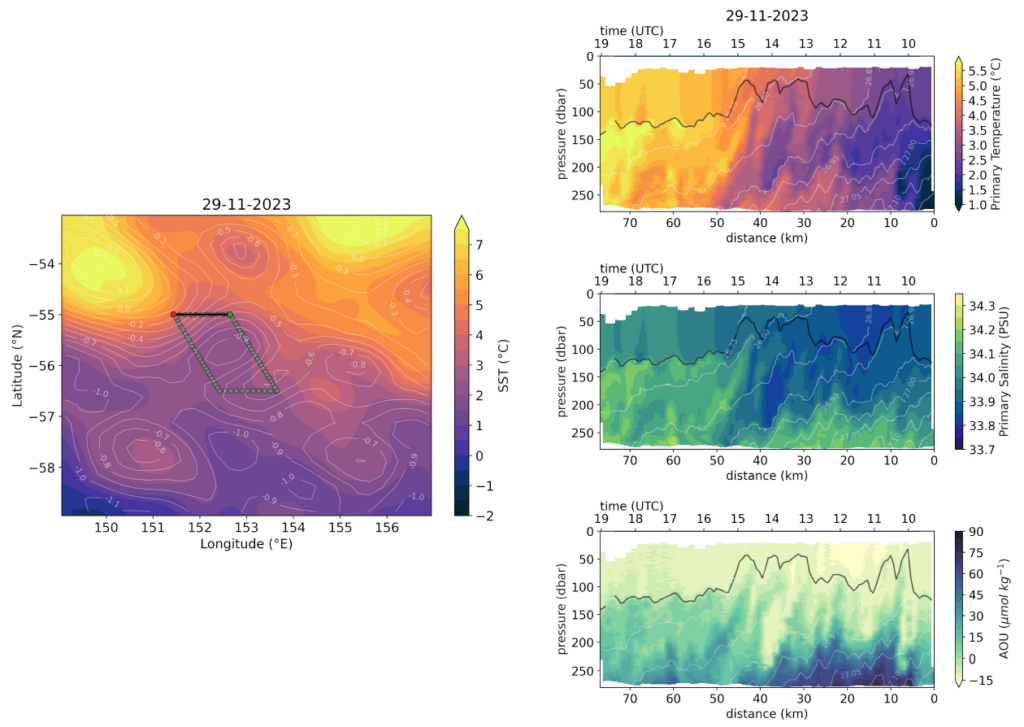

Whenever the orbit of the SWOT satellite starts heading towards us, we roll out a black and yellow rectangular frame called a Triaxus – about the size of a large freezer – and carefully lower it into the Southern Ocean behind CSIRO research vessel (RV) Investigator. Then we tow it, at about 8 knots for at least 18 hours, while the satellite’s radar altimeters are paying attention to the surface of our patch of the ocean.

The Triaxus is equipped with a host of different sensors to measure the physical properties of the water like temperature, conductivity, pressure and light penetration, as well as biochemical properties such as oxygen, chlorophyll, and nitrate concentrations. The Triaxus has an optical particle counter and an underwater camera so we can watch what it sees from the operations room inside the ship.

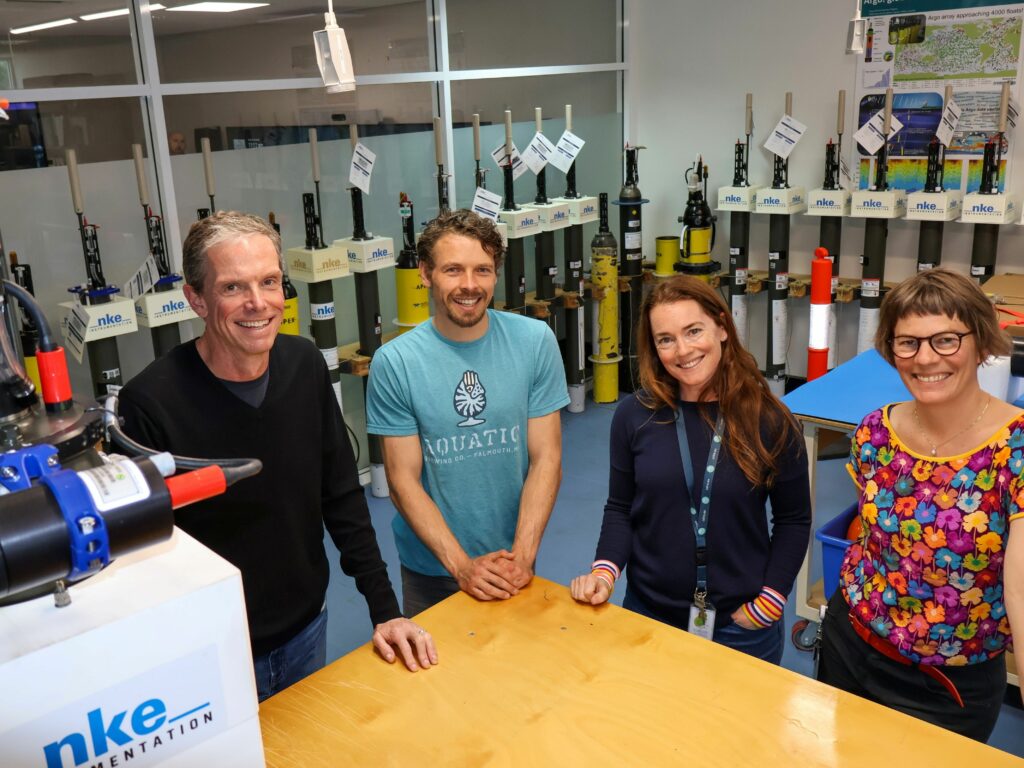

Also carried on the Triaxus frame is equipment overseen by Dr Kurt Polzin from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. His three-pronged device is a 3-D current meter, like a speed gun for water. With it he hopes to track the micro-turbulence happening inside the water column on a smaller scale that can be detected by a satellite mapping the surface.

Kurt says towing the Triaxus is like flying a drone through the atmosphere, with the current meter trying to detect wind gusts. To make sense of the data gathered by the current meter underwater, the movement of the Triaxus through the ocean has to be taken into account through some mathematical processing which enables any fine-scale turbulence to be defined.

As the Triaxus is towed, it follows a pre-programmed flight plan that allows it to undulate up and down through the top 300m of the water column. It sends data back to the ship in real-time and is constantly monitored by someone on board who can communicate with the Triaxus and control its ‘wings’ to adjust its flight plan.

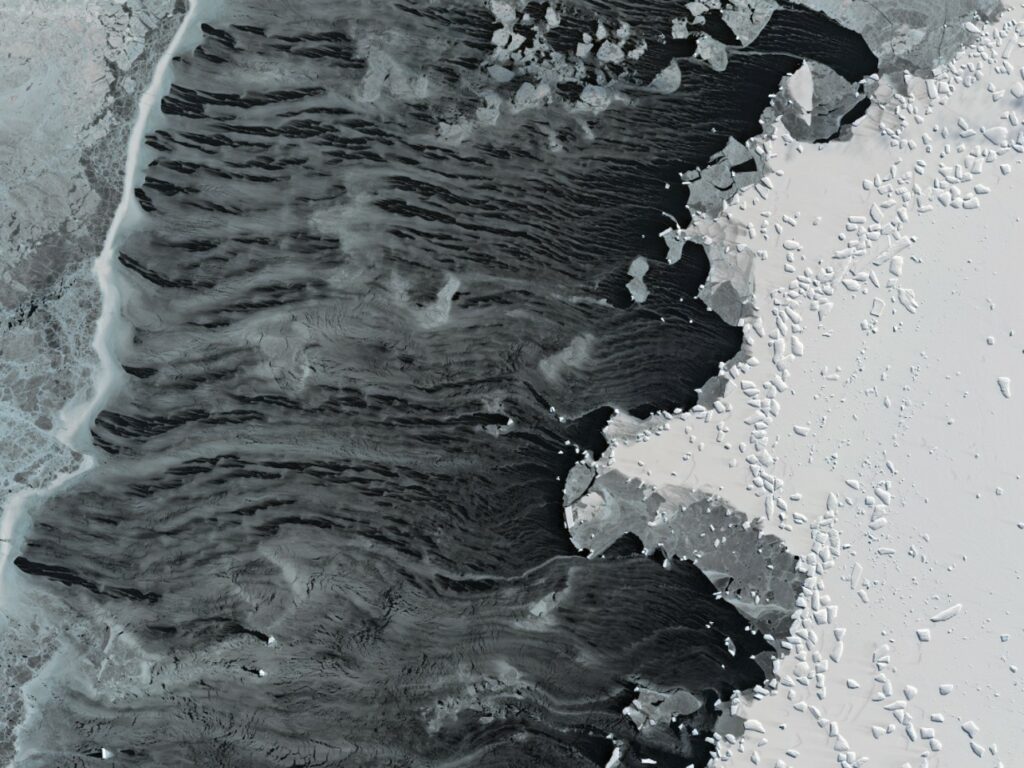

One of the great things about the Triaxus is that it can survey large distances in a short period of time and acquire high-resolution data, immediately visualised on board. We can also identify fine-scale features in the ocean both horizontally and vertically. This makes it an ideal instrument to use in partnership with the SWOT satellite, towing it through the swath mapped from space. Together these highly efficient data-gatherers allow us to relate the fine-scale features measured by the satellite as it passes overhead with the upper ocean features measured by the Triaxus.

During the FOCUS voyage, we have also deployed a number of autonomous instruments, such as floats and gliders, that survey the ocean from the surface down to 1000-2000m. Each of these come with their own set of sensors and capabilities. For example, the floats are designed to drift with the currents as they profile, and therefore help us understand how features in our ocean evolve as they’re carried downstream. However, we have no control over their trajectory and they can also be challenging to interpret, particularly if the oceanic features are evolving rapidly in space and time.

Triaxus data are typically more straightforward to interpret, as it is towed along a straight transect behind the ship and can capture features up to 100km apart all within the same day. It offers a cross-stream view of the ocean that complements the along-stream perspective from the floats and other autonomous instruments. This allows us to put together a three-dimensional understanding of the fine-scale features within this highly energetic part of the ocean.

Maya Jakes is a PhD student at the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies, UTAS.

This research is supported by a grant of sea time on RV Investigator from the CSIRO Marine National Facility which is supported by the Australian Government’s National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy (NCRIS).