Living the oceanographic dream

by Polina Sholeninova

When I was in high school in Russia, I was thrilled by this vast body of water covering most of the planet’s surface. I chose to pursue a degree in oceanography because I loved the ocean and dreamed of being at sea, participating in scientific voyages, and discovering the unknown. Back then, oceanography wasn’t very popular. Out of the 20-something people who studied with me during the first year of undergrad, only three of us chose oceanography. The others went on to study meteorology or hydrology.

Anyway, I finished my undergrad studies, but without an opportunity to go to sea. It was difficult to get on a ship in Russia, especially for girls. I think this, along with the general state of research in the country, dampened my enthusiasm at the time, and I lost motivation for a while. After a few years, I decided to continue studying and went to Finland to pursue a master’s degree in oceanography. The research there mainly focused on the Baltic Sea and, to some extent, the Arctic Ocean. For someone wanting to study blue oceanography, opportunities were limited, so I started seeking PhD projects outside Finland. Australia, always seen as a very remote (almost unreachable) island continent, suddenly seemed like an obvious place to study oceans. My master’s thesis supervisor from Finland, who had worked in Australia for 10 years, also supported and encouraged my choice. And here I am.

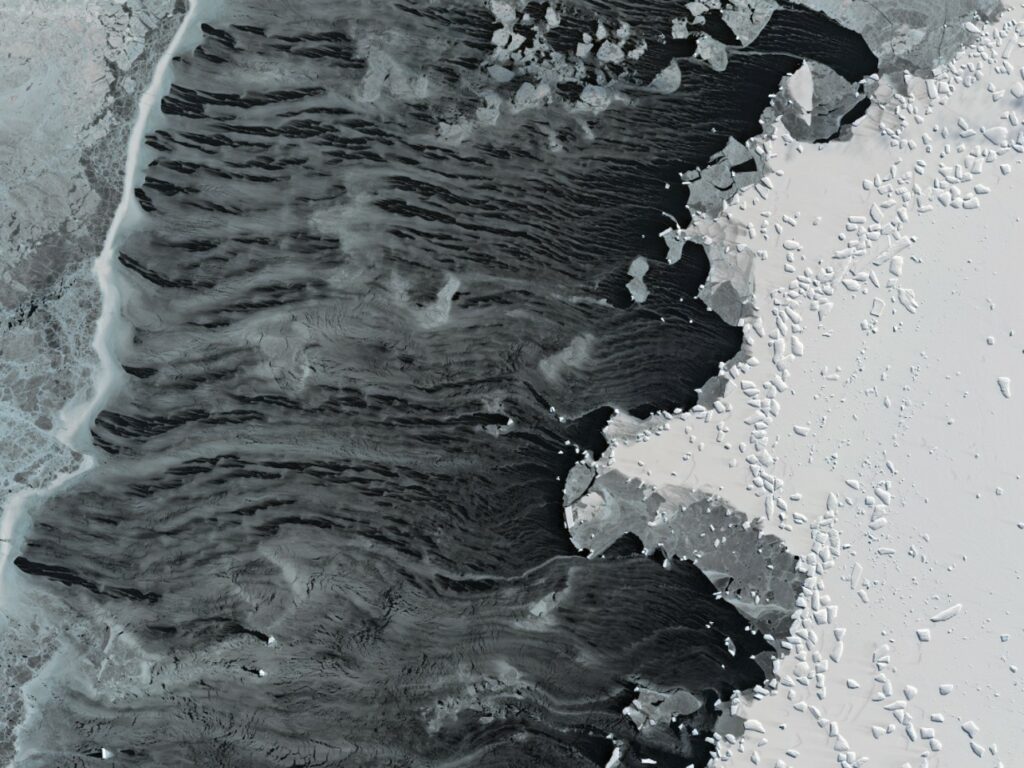

My PhD project at the Australian National University focuses on Antarctic Bottom Water – vast masses of cold, dense, salty water originating around Antarctica and driving the global ocean circulation. By moving heat, carbon, oxygen and nutrients, Antarctic Bottom Water is a key influencer of the planet’s climate, carbon cycle and biodiversity.

More than two weeks have passed since we boarded CSIRO research vessel (RV) Investigator. What can I say so far? It took some time for me to adjust to the environment: being on a constantly moving and rolling ship, adjusting to 12-hour shifts from 2am-2pm, working closely with new people, and living away from your normal routine and home is something you would expect to take time to get used to.

I’m very happy that my sea legs have grown. As soon as we left the calm waters near Hobart, I realised the only position where I didn’t feel the urge to throw up was horizontal. The sea was rough for a few days of our transit, and I just slept in my cabin without being able to have proper meals. Sometimes I thought I might end up being seasick the whole voyage (I’ve heard real stories from people who were), but I kept believing in my body’s ability to adjust. Eventually, it did (after the first week).

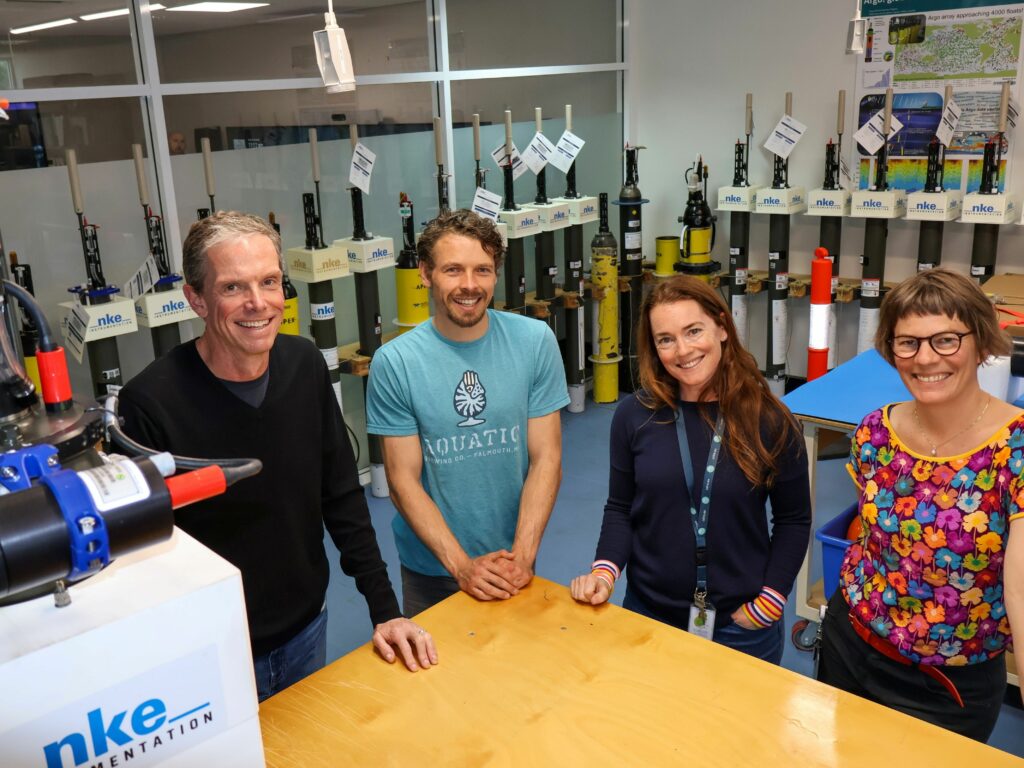

On this voyage, I and the other students are mainly busy with CTD deployments. The CTD stations are located close to each other: by the time we recover the rosette at one station and finish sampling its bottles, the ship arrives at the next station, and the deployment starts again. Sometimes we stop CTD casts to deploy other instruments (moorings, drifters, gliders, Triaxus). On days like this, we have more free time, and we can watch how the instruments are deployed. Some days, the weather disrupts operations, like today when I found time to write this blog.

The most precious thing for me on the voyage is actually getting hands-on experience with how oceanographic data are collected. As a PhD student and someone working in the space of numerical modelling, I always get lost in the data. With computational challenges, and my own topic, it’s easy to forget why I compute what I compute, to look at the bigger picture and how my area of research is related to the ocean, climate, our lives, and why it matters for me to study what I study.

During the voyage, everything has gained new meaning for me. I see how much money and planning goes into organising this five-week (short compared to a human lifespan) voyage to study a small 200×100 km area of the ocean. It reminds me of how much effort and passion people put into it, to leave their lives and families on land and go to sea, where they must stay focused, calm, and dedicated to their work every day: not only scientists but also the supporting crew, cooks, everyone.

And this isn’t even the longest voyage. If you go to Antarctica, the transit alone takes several weeks, and the conditions there are much harsher, with operations facing far more challenges. The collected data then go through processing and are published to open-access archives, from where I’ve downloaded data many times during my studies. Now I see what it costs to get these data on the servers, and it reminds me of the importance of the work we all do.

It also makes me realise how far I’ve come. I remember when I was an undergrad and we were chatting about sea expeditions with peers, people said that Australian voyages are known for being very well-organised and how difficult it is to get on an Australian research vessel. And here I am, 11 years (eight excluding gap years) since I started studying oceans, on an Australian research vessel. This experience will certainly impact my future work and keep me motivated during challenging periods. I believe that every student in oceanography should have this experience at least once in their career, whether they continue an academic path or not. I hope it will be as thought-provoking and insightful for them as it is for me. I am also enormously grateful to my supervisors for bringing this opportunity to me and to everyone at CSIRO and AAPP who made this voyage possible.

This research is supported by a grant of sea time on RV Investigator from the CSIRO Marine National Facility which is supported by the Australian Government’s National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy (NCRIS).